Chuck Webster

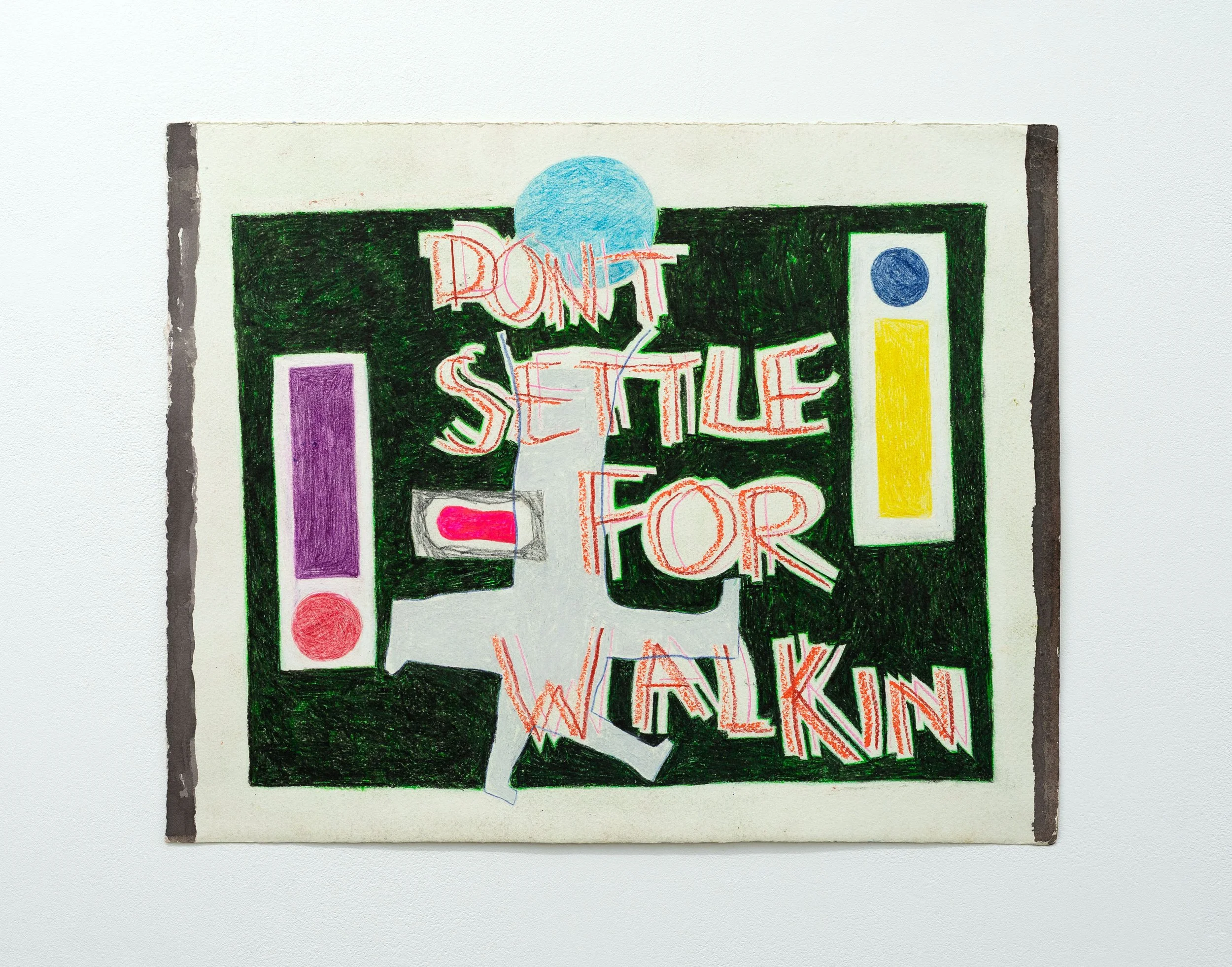

Hunted Projects is delighted to present this interview with Brooklyn-based artist Chuck Webster, held on the occasion of his new solo exhibition, Don't Settle For Walkin'. The conversation explores Webster's dynamic drawing practice and the themes that shape this body of work - accumulation, intimacy, and the vital energy embedded within materials and marks. Created through sustained sequences of attention and improvisation, Don't Settle For Walkin' transforms fragments of language, memory, and observation into dense, irrepressible meditations on how images exceed their limits. Celebrating Webster's first solo exhibition in Scotland, this interview offers intimate insight into an artist for whom drawing remains a living practice - a site of discovery, freedom, and encounter where every gesture holds the possibility of something unfamiliar asserting itself.

Hunted Projects: Can you tell me a little about yourself and your background?

Chuck Webster: I grew up in upstate New York, the child of an English professor and an art historian and print curator, so I was lucky enough to be exposed to art, antiques, literature, film, and history. I have many memories: climbing the rocks of Stonehenge, visiting Giverny, the Louvre, and the Maeght Foundation at 14, seeing the Manet retrospective in 1982 at the Met Museum, and making my first oil transcription of The Balcony. I drew constantly and saved everything. I published a batch of those drawings as a children’s book in 2015, called 43 Monsters, with text by Arthur Bradford.

I went to Oberlin and American University, and learned to paint by working from observation, painting landscapes and drawing endlessly, everything from Ruisdael to de Kooning. I filled hundreds of sketchbooks. I learned to study and construct pictures on the deepest level, to the point where there was a slight understanding of how pictures function. We would draw sitting in front of Rembrandt’s Lucretia for eight hours, and only then begin to grasp its true nature. Then the next day, it was a mystery again. The greatest pictures remain new and indecipherable, like Titian’s Flaying of Marsyas, and that is the point.

After grad school, I came to New York. I have been working and showing there ever since. It is a marvellous journey, and I have maintained a deep curiosity and determination, always trying to keep working and learning. I find that things I make today echo work from 30 years ago, and that there is always so much more to know. These drawings are a fresh example of that.

Hunted Projects: Can you tell me about your current studio and working routine? Do you have any rituals or habits that contribute towards a productive day in the studio?

Chuck Webster: I work in a space of about 800 square feet in Brooklyn. I always say that it is insanely small, as I want to work on drawings that are two to three meters long in the same manner as these. I’d need a 50-foot wall to do that. I have it well organized, with about 15 flat files full of work, a painting rack, a good stock of supplies, and two big painting walls. I keep a lot of books, too. When I get to work, one of my rituals is to pull one from the shelves and leaf through it, getting inspired. It may be on Russian embroidery, Robert Frank, or Rammellzee, or it might be an artist I was thinking of as I drove to work. I have a coffee, look at books, and glance up at the paintings to see what has happened. Then I usually sweep and tidy up a bit before really starting to paint.

I’ll assign myself a set of tasks on different paintings. My panel pictures are very labor-intensive, so there is always a ton to do, and I always feel behind. But this plan always gets changed quickly into something new.

Hunted Projects: To what extent do you consider your city as being an influential factor in the shaping of your work? Do you feel that your surroundings have influenced you in one way or another?

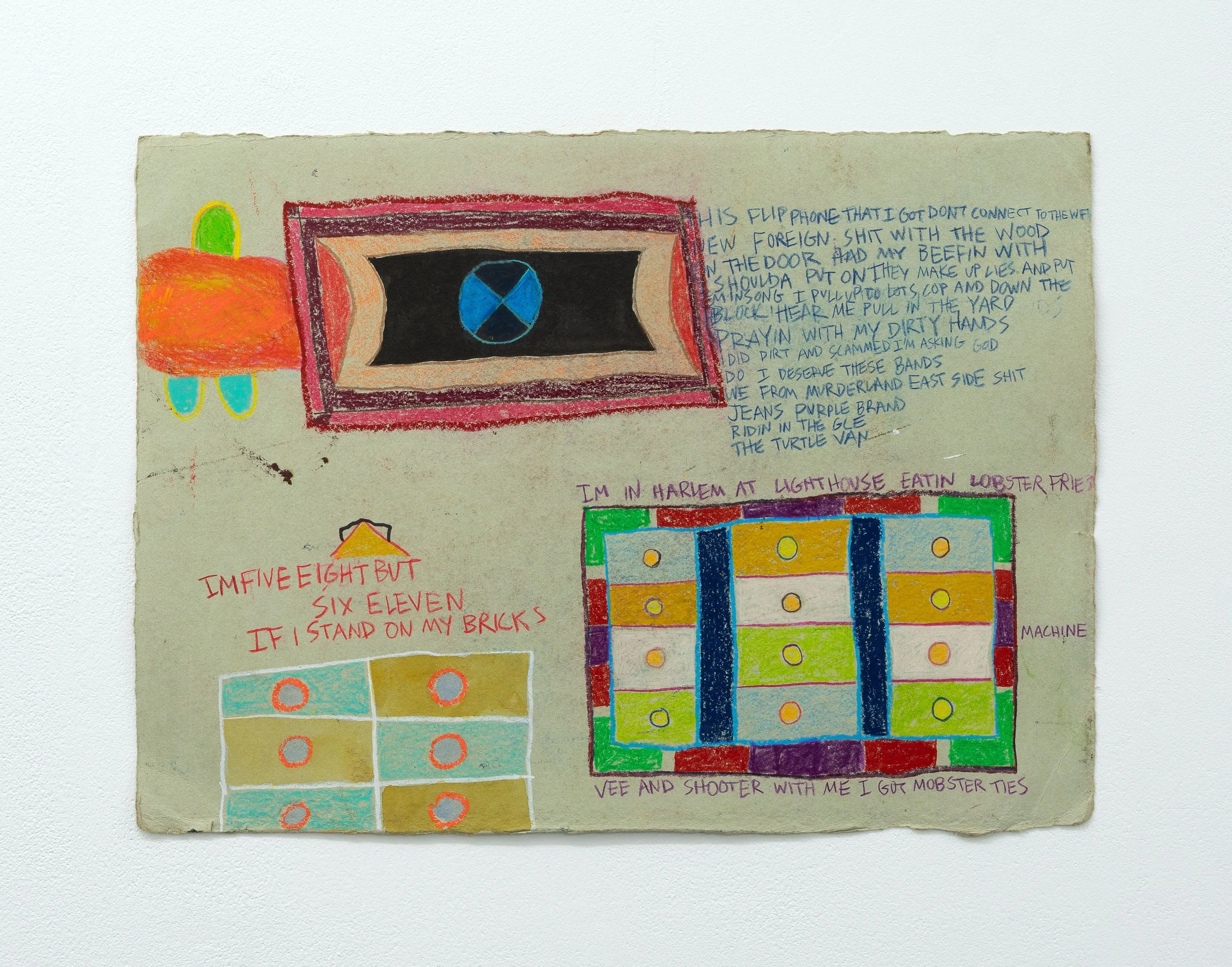

Chuck Webster: New York City is a huge influence on all aspects of my work. I love the energy of New York, the people, the spirit. There is a Black Star hip-hop song called “Respiration” that goes, “I can feel the city breathing,” and I believe that with all my heart. The city exudes life, art, and toughness. I love New York graffiti, the museums, the urban folk art, the sports, the strange little stores, and the characters I see every day. It inspires me to work harder.

Hunted Projects: This group of drawings was made between 2022 and 2024 and described as a period of rapid, almost wave-like production. How do you understand this moment within the larger arc of your practice?

Chuck Webster: I don’t think it differs that much from any other period of work inasmuch as I am just trying to continue along as always. It’s no different than any other big drawing wave, and I hope it keeps going. There are different adjustments of scale and process, but it’s mostly the same as always.

Hunted Projects: You invoke Philip Guston’s idea of the “peculiar miracle” of artmaking, something that resists explanation and insists on experience. How does this idea inform your relationship to meaning and interpretation in these drawings?

Chuck Webster: I have always had a practice of drawing in succession, drawing “through” ideas, until something else emerges from the practice, something mysterious and unfamiliar. I believe that is what Guston spoke of. The same process happens in painting. Who knows how certain ideas come into your head? Where do these things appear? I don’t need to answer these questions; it just has to happen over and over again.

Guston has many incredible quotes and essays on art. There is a good collection of them available. He would talk about working until the forms felt “irreversible; the only way, at this moment, the painting could be.” The forms, which touch and bump and overlap each other, strain to separate themselves, yet cannot exist without one another.

What a standard for art. What a way for a painting to be a concentrated area of spiritual energy, a site of a ceremony of faith in practice. That’s what I think he meant by a “peculiar miracle.” I am less interested in understanding that miracle, the third thing between the self and the painting that occurs sometimes, than in experiencing it. I want to be baffled and confused by it.

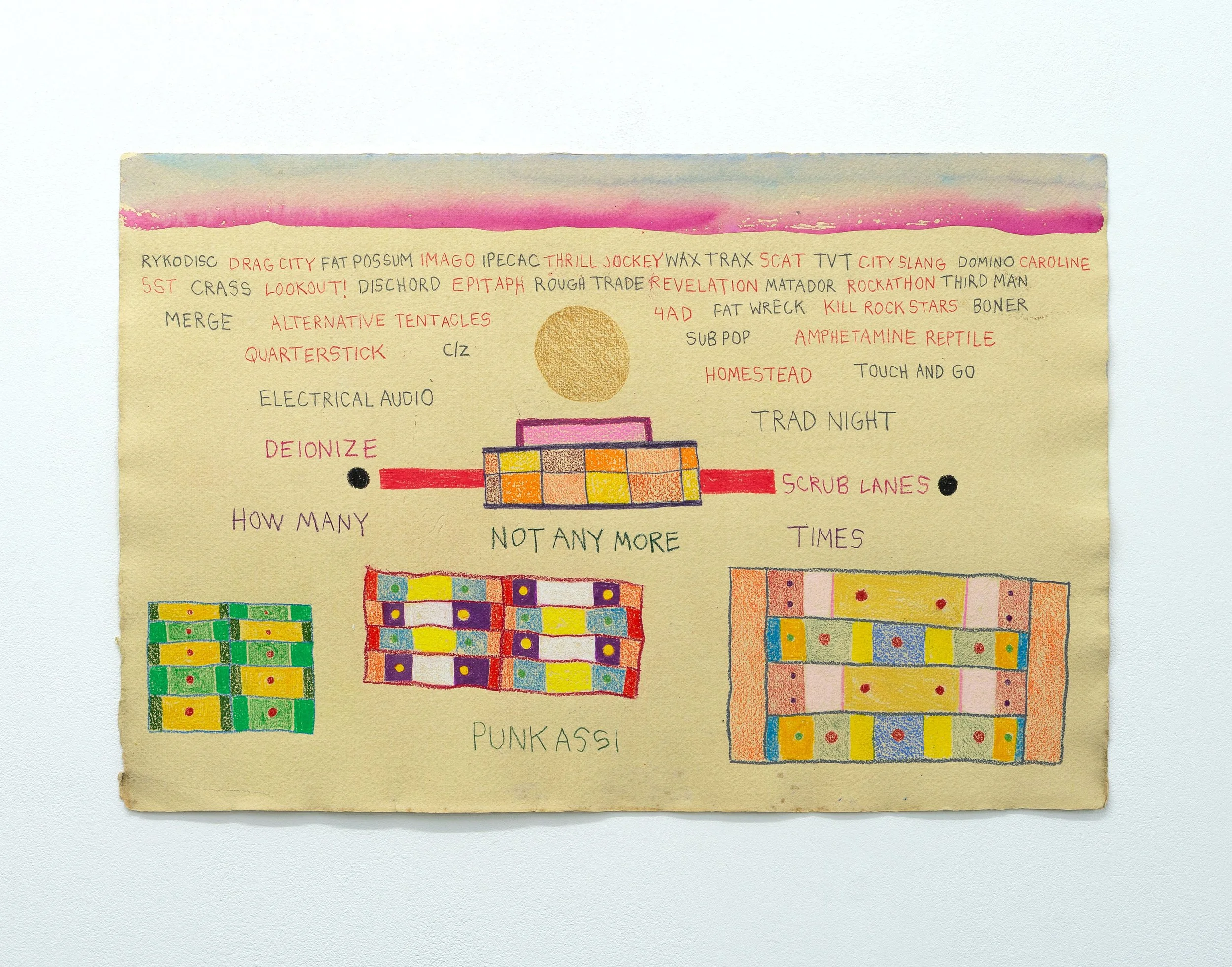

Hunted Projects: Your work draws from an expansive field of references, spanning art history, folk traditions, architecture, music, literature, and everyday visual culture. How do these influences operate collectively within your process, and how conscious is their presence as you work?

Chuck Webster: The influences are always present. I look at books while I’m working, think of new things and laugh out loud, and look at Genius.com a lot lately to get musical references correct. I work in a kind of open, curious mind state, where I might suddenly think of a certain form in a print by Hercules Seghers or the characters in Trenton Doyle Hancock’s work, use them in what I’m doing, move a brush a different way, and choose a new colour. Louise Bourgeois said she paid so much attention to getting the colour, mark, scale, and touch of her work right that she forgot about content and references. That happens to me, in that I forget what the reference is and can only pay attention to the colour and thinness of the pencil line.

Then again, all references may disappear, and I’m completely confused and baffled by what I’m doing, which is great.

Hunted Projects: Language re-enters your drawing practice here after a twenty-year interval. What prompted its return, and what role does text play now that differs from your earlier engagement with words?

Chuck Webster: I don’t think it has changed that much. There were echoes of what I am doing now back then: lists, lyrics, nonsense words. This time, I think all the floodgates have opened, and I am increasing scale, which is a marvelous thing. They are built just as any other drawing I have made, as a process of the hand, heart, eye, and mind upon a piece of paper to make a picture. Over the last three years, I think the scale has gone up, and I am spending more time on each one, with more freedom and confidence.

I read that Alex Katz would do dozens of studies of his giant, loose landscapes in advance so that he could dance through the painting like Fred Astaire and finish it in a few hours. I’d like to be at that point, on a 10-foot drawing, where I can maintain that level of self-trust for months. Drawing all the time helps with that.

Hunted Projects: You work extensively with rare and vintage handmade papers, which you actively collect and maintain long-term relationships with. What draws you to these specific papers, and how do their material qualities, histories, and modes of making contribute to their significance within your practice, both conceptually and experientially?

Chuck Webster: In 1996, I was lucky enough to have my mom buy out the remaining stock of Arches 200 lb. hot pressed watercolour paper from a local store. I had enough to really get to know its advantages. When I got to New York, I discovered New York Central Art Supplies, the best paper store in America, and they displayed samples of each paper for people to touch. That allowed me to truly learn about all of them.

I then began buying 19th-century paper and journals on eBay, largely because the paper simply felt better to the hand. It has an unbelievable touch and is strong enough to be dunked in water and left outside for days and still be fine. It has a kind of material resistance and a spiritual energy. I subscribe to what Bill Jensen says about art supplies: “One of my jobs as an artist is to release the energy that exists in materials.”

I do love the history and the process of making paper, just as a car aficionado loves cars. It is a miraculous process, very similar to making paint. It can also be used as an art material, just like watercolour, oil, or clay. I also have many great friends who are papermakers, and there’s a wonderful community and tradition going back thousands of years. It’s a marvelous process, not unlike making paint, which I do as well and highly recommend for any artist.

Hunted Projects: Many of the textual fragments come from music, poetry, film, and popular culture, often carrying strong emotional or cultural associations. What qualities make a phrase resonate enough to become part of a drawing?

Chuck Webster: It could be anything; it’s most often something that has resonated with me. I like the way certain words sound, and the obscurity and humor of specific kinds of language used in certain professions or companies. I also have a lifelong obsessive memory for song lyrics and a very completist attitude about music. It’s so joyful for me to write them into the work, for reasons I don’t understand. These drawings are just a blast to make. They are completely baffling to me, and that’s the best way to be.

Hunted Projects: These drawings balance speed and accumulation, intuition and structure. How do discipline and play function together in your studio practice?

Chuck Webster: Those two things are always there, in the spirit of Klee. In graduate school, I made incredibly detailed ink landscapes and small, funny paintings of abstracted pinball machines. One day, a visiting artist, John Walker, stuck a bag of Skittles into one of my drawings and said, “Why not do both?” I worked from observation, creating strange new worlds from the landscape and inserting whatever I wanted, grabbing things directly from what I saw. I have done that ever since. Those two things are always present: sharp observational discipline and innocent play.

Hunted Projects: Several works in the exhibition contain no textual references at all. How do you think about absence, silence, or non-verbal meaning within the larger body of work?

Chuck Webster: All the drawings function in the same way, with or without text. If the picture asks for words, words will happen naturally while making. If not, they won’t.

Hunted Projects: Although these drawings are physically modest, they engage ideas of scale, density, and presence that recur throughout your practice. How do you think about scale in relation to intimacy and abstraction?

Chuck Webster: I think a lot about body scale, about how you can enter a picture both as something you can hold in your hand and as something you can step into. To return to Guston, a loose quote is: “You start painting the house, it turns into a moon. You start painting the moon, it turns into a shoe. You start painting the shoe, and it turns into a loaf of bread.” I am looking for a situation where all of those can be true at once.

Hunted Projects: You describe drawing “in and of the world museum,” suggesting a practice rooted simultaneously in art history and lived experience. How does this position shape your understanding of the artist’s role today?

Chuck Webster: That’s a good question. To make things worth the time and attention of others, the artist must be dedicated and involved with the work on a very intimate and primeval level. The paintings must have their own emotional world.

I am very interested in crafts, woodworking, and cooking and revere those great artists for their dedication and talent. This leads me to a book by Bill Buford, Heat, where he learns to cook in a prestigious New York restaurant. They have him cutting carrots, and he must cut them all into quarter-inch cubes. He works for hours, picking out all the wrong sizes, and the chef casually tosses them into the pot and asks for more. When he asks why they need to be so specific, the chef laughs and says with all seriousness, “Well, they are going to be served to people.” That amount of work was a small price to pay for the honor of cooking for others. I want the work to embody that kind of discipline and emotional life, so that it forms its own relationship with the audience. My role is to make it worthy of their attention.

Hunted Projects: Any last points or thoughts you would like to share?

Chuck Webster: I think that drawing forms the basis for my work, as I can cycle through hundreds of ideas easily, and this forms the basis for decisions made on large paintings. The drawings have always been the basis for how I make art, and how I survive in the world. For me, it is how my mind breathes. I’m glad these drawings are being exhibited in Edinburgh at Hunted Projects, and I hope they bring you joy. Please feel free to laugh out loud.